In Peter F. Hamilton’s Pandora’s Star, humanity colonized over 600 planets without ever inventing long-distance spaceships. People travel between worlds in ordinary trains through hyperspace wormholes: two young researchers created the first portal in their lab in 2050, after which outer space travel became unnecessary.

The idea is hilarious: almost every sci-fi book includes hyperspace travel, since it’s the only quasi-scientific way we can imagine going faster than light. But for some reason, people always do it on starships. Why, indeed? If we invented hyperspace wormholes, why not build them on the planet’s surface? Sure, you can come up with some mumbo-jumbo explanation, but it won’t be any more convincing than just assuming we can. Hamilton’s idea of traveling through the galaxy on diesel trains is refreshingly plausible.

What’s less convincing is the colonization of 600+ planets, many hosting billions of people.

Living on distant planets and building a federation of habitable worlds across the galaxy has been a dream for decades. We used to think the main hurdle was transportation. But is it?

Even if a couple of young geniuses invent hyperspace travel by 2050, we still won’t be able to truly populate even a handful of habitable worlds—we just don’t have the people. Global population growth is slowing year by year. It peaked in 1963 and has been declining since; according to current projections, world population should start shrinking by the end of the century after hitting around 10 billion.

Fertility rates in developed countries have already dropped below replacement level and keep falling. The looming threat of depopulation is discussed constantly in blogs and opinion pieces. There are hundreds of posts on the topic, but most are just culture war extensions: one side blames inadequate childcare subsidies, the other decries moral decay and blames radical feminists.

Are feminists really to blame? Can more generous childcare subsidies lead to more babies? To answer that, we need to think clearly. The best approach is economic: analyze the costs and benefits of having kids.

Economic theory says production levels are set by marginal revenue and marginal cost. Marginal revenue is what you earn from selling the next unit; marginal cost is what it takes to produce it. You stop producing when your marginal cost equals or exceeds your marginal revenue. If you build cars, you stop when the next car costs more than it brings in. Keep going after that and you lose money.

Having children follows the same logic. Women stop when they feel the next child will cost more than it’s worth to them. To understand when that happens, we need to know what the costs and benefits are.

The most obvious benefit is the joy of parenting, instilled in us by nature. People feel overwhelming happiness when they see a child extending their genetic line. It’s always been that way.

Children also expand your social world: you meet other parents, grow your network, and gain new life opportunities.

Other benefits are less enduring.

In the past, up until the mid-20th century, the main benefit of having children was social security. Children functioned as a pension fund. People invested in them during their economically productive years, and when they grew old and could no longer work, their grown children supported them. But today, with the welfare state and pension systems, that benefit has vanished. You simply pay taxes or social security contributions, and once you retire, the fund you paid into—or society as a whole—supports you financially for the rest of your life.

Another historical benefit of having more children was closely tied to this. Until quite recently, even the most developed countries had high child mortality rates. Your children had a good chance of dying before reaching adulthood. To account for that, people tended to have more children—often more than was statistically necessary—because no one could predict whether their own children would die more or less frequently than average. It made sense to overcompensate, just to be safe.

Finally, there’s observance—the sense that you’re doing what’s right or expected of you by a higher authority, usually God.

Now, the costs.

First, being a parent comes with significant direct financial costs. In the U.S., the average annual expense of raising a child is $29,419—almost a quarter of the average family income.

But that’s just the beginning. Women with children earn significantly less than childless women, simply because they can’t devote as much time and energy to work. Fathers, interestingly, earn slightly more than childless men—the reason isn’t entirely clear. Still, the “father bonus” doesn’t make up for the “mother penalty”: even with tax breaks, families with children earn on average 12–13% less than childless couples.

Second, pregnancy, childbirth, and breastfeeding are physically demanding and take a toll on the mother’s health—not to mention her long-term physical attractiveness.

The lactation period is also a major psychological stressor for both parents due to chronic sleep deprivation.

Then there’s the emotional stress: children get sick, disappear for hours and don’t answer their phones. That kind of thing happens often and wears parents down.

Finally, there are the opportunity costs. Time spent raising children could be used for countless other things—partying with friends, going on romantic vacations, watching movies, or studying to advance your career. Women with children, on average, have lower education levels than childless women.

So how do these costs and benefits stack up at the margin?

We know from both data and experience that the benefits of having a first child generally outweigh the costs.

The marginal joy of a second child is lower—by then, you’re already a parent—but still meaningful. And the marginal cost of the second child, while high, tends to be lower than the first, especially if they’re born close together: if they’re the same sex, they can share clothes and toys, and even if not, they can still share a stroller. Parents usually don’t need a bigger home for at least 12 years—both kids can share a room until one hits adolescence.

But the population replacement level is 2.1 children per woman, and since no one can have 0.1 of a child, some couples need to have three.

That’s where the real problems start.

First of all, by the third child, the joy of having another baby diminishes noticeably. You’re already a parent twice over; becoming one again still feels good, but not nearly as exciting as the first or second time—at least for most people.

At the same time, the financial strain rises sharply.

With a third child, the father bonus disappears—employers apparently feel that a wage boost for the first two was generous enough. The mother penalty, on the other hand, increases significantly: women with three or more children earn considerably less than those with one or two.

Also, economies of scale begin to reverse.

While the second child tends to cost less than the first on the margin, the third costs more. If the third child comes soon after the first two, there’s often less opportunity to reuse clothes and toys due to wear and tear. If there’s a big gap, those items are usually long gone. And with a third child, most families need a home with an extra bedroom—and almost always a larger car. Most hatchbacks and sedans, especially in Europe and East Asia, can’t accommodate three child seats or two seats and an extra passenger in the back.

To sum it up:

The first child is a huge emotional boost, but it costs a family roughly a third of its income, once you factor in lost earnings from the mother penalty. It also means sacrificing about 15 years of full-scale social life. Still, judging by birth rates, the vast majority of people think it’s worth it.

The second child costs slightly less on the margin, but together, two children account for 40–50% of the average family’s income. Many still see that as a fair trade for the joys of parenting—but not the majority. In most developed countries today, more than half of couples believe one child is enough.

With a third child, you're more than twice as badly off financially as couples without kids. And you can forget about spending your time according to personal preference for the next 20 years. Only a small minority of modern couples believe that’s a good bargain.

This all but destroys any realistic hope of maintaining functioning social security—let alone colonizing hundreds of distant worlds.

Can anything be done about it?

Both current mantras—“Increase subsidies” and “Cancel radical feminism”—are going nowhere.

First, subsidies. The state simply can’t cover the marginal cost of raising a second or third child, which runs $40,000 a year—or $50,000 if you include lost maternal income—for 18 years. Even $20,000 a year for 10 years is not financially viable. That money has to come from somewhere, and the only real source is taxes on the same families receiving the support.

You could try taxing childless families or one-child families instead, but the required tax hikes would be so steep they’d topple any democratic government that attempted them.

Smaller subsidies won’t make much of a difference either. If the support doesn’t cover at least half the marginal cost of raising another child, it won’t tip the balance for most families.

We already have plenty of examples. So-called “generous” financial incentives—amounting to a few thousand dollars over two or three years at best—might cause a small birth rate uptick for a year or two, until couples realize it doesn’t fundamentally change their financial reality.

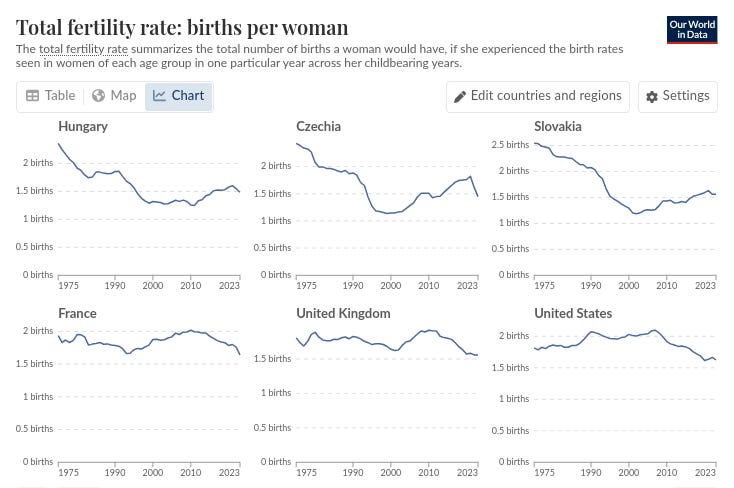

Hungary, for instance, has rolled out a wide range of mother support programs, widely praised in the conservative press. Yet its fertility rate remains stuck at 1.5—roughly the same as Czechia or Denmark, and lower than France or the U.S.

We don’t even need to look at the costs to see that subsidies won’t solve the problem—just look at global fertility rates. In wealthy countries, fertility is much lower than in poor ones. If lack of money were the main reason people avoid having children, it would be the other way around. In fact, American statistics alone make this obvious: the poorer the family, the more children it tends to have. Birth rates in families with incomes under $10,000 are about 25% higher than in families earning $200,000 or more.

Interestingly, the proportion of women who don’t work follows a U-shaped curve relative to household income. Women are most likely to stay out of the workforce in the poorest and richest families—but for entirely different reasons. In poor families, women often stay home because they can’t afford childcare. In wealthy families, the husband’s income allows the wife to pursue a preferred lifestyle, which, more often than not, doesn’t include more than one child.

This brings us to the argument that the root cause of fertility decline is liberal, Western, feminist culture.

Alas, the data doesn’t support that claim.

What do Puerto Rico and Singapore, Italy and the United Arab Emirates, or Finland and Costa Rica have in common?

Each pair has nearly identical fertility rates, all well below the replacement level of 2.1. Puerto Rico and Singapore: ~0.95. Italy and the UAE: ~1.21. Finland and Costa Rica: ~1.3.

The problem of low birth rates isn’t specifically Western or liberal. Fertility is falling in nearly every high- or even middle-income country. The Arab states that some conservatives tout as fertility havens are no exception: birth rates have dropped below 2.1 not only in the UAE, but also in Kuwait (1.5), Qatar (1.7), and Bahrain (1.78). Only Saudi Arabia (2.29) and Oman (2.48) remain above that line—and even there, the number of children is dropping rapidly. They’ll likely fall below replacement by the end of the decade.

Even in the theocratic Iran, where women have virtually no rights, the fertility rate is just 1.67.

In fact, the Scandinavian countries—arguably the most secular and liberal in the world—have higher birth rates than the more religious and traditional nations of Southern Europe or Latin America. That’s not a coincidence.

In recent decades, economic development in the Global South has been remarkably fast. In just 40 years, East Asia went from one of the world’s poorest regions to one of the richest. The same applies to the oil-rich Gulf states. Elsewhere in Asia and Latin America, countries aren’t ultra-wealthy, but per capita incomes have increased several times over. Today, most Asian and Latin American women can reasonably expect not to end up begging on the streets—even if they never have children.

But while the economies have modernized, cultural transformation has lagged behind. People suddenly have far more money than their parents did, but their parents are still alive—and still hold traditional views.

And those traditional views place the full burden of childcare on the mother. Husbands aren’t expected to do much beyond earning money and serving as role models for their sons.

That’s not all. In traditional societies, women are also expected to handle all the housework and care for their own elderly parents as well as those of their husbands. Add raising children and holding down a job—because without it, the family income would be nearly cut in half—and the result is a massive workload. Most Asian women no longer want to carry that burden, so many choose not to have children, and often not to marry at all.

That’s why in Southern Europe, East Asia, and parts of Latin America—countries that are wealthy or at least reasonably well-off—birth rates today are significantly lower than in Western Europe and North America. In the “old” First World, economic development happened earlier, and cultural adaptation had more time to take root. Husbands are now expected to share the responsibilities of childcare and housework—maybe not equally, but at least substantially. Because women aren't completely overwhelmed, they’re somewhat more willing to have children. This helps keep fertility rates higher, though still below replacement: husbands, too, don’t want many kids, since they also have more appealing ways to spend their time than raising a second or third child.

The fertility crisis isn’t limited to the godless, liberal West. It’s global—and it affects societies of every culture and religion. India, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Peru all have birth rates below 2. Laos, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Morocco, Guyana, South Africa, Paraguay, and Guatemala are still slightly above 2—but most will fall below that by the end of the decade.

Outside of Africa and the poorest, war-torn parts of Asia, only one country has a fertility rate above 2.5: Haiti. And even in Africa, fertility is plummeting.

Now it’s time to address the elephant in the room: Israel.

Israel is the only developed country with a comfortably above-replacement fertility rate—around 2.8, higher than in any neighboring Arab country. Even more striking: the birth rate of Israeli Jews is higher than that of Israeli Arabs, and only about 5% lower than that of Palestinians. And while fertility rates among Israeli Arabs, Palestinians, and Arabs in nearby countries are rapidly declining, fertility among Israeli Jews is rising—if only slightly.

Israel does provide child subsidies, but they’re not significantly different from those in European countries, where fertility is almost half as low.

So why do Israeli families have more children?

Conservatives usually credit the ultra-Orthodox Haredi community’s sky-high birth rates, along with a general “Jewish family culture.”

It’s true that the Haredim have very high fertility—on par with Somalia’s—around 6.5. But they make up only 12% of Israel’s population, and their fertility is dropping just as quickly as in many African countries: at the start of the 21st century, it was 7.3.

Israel’s high birth rate isn’t driven by the Haredim—it’s driven by the majority of the population. Among all Jewish groups except the fully secular, fertility is 2.5 or higher—and growing. Even ultra-secular Israelis have a birth rate around 2, comparable to that of India or Vietnam.

So... is it the famed Jewish “family culture”?

Not really. American Jews have fertility rates almost exactly half those of their Israeli counterparts across all religious groups: about 3.3 for the Orthodox, down to 1 for the non-religious. The overall fertility rate for American Jews is actually lower than that of the average American. So “Jewish family culture” doesn’t explain Israel’s high birth rates either.

I’d guess the real reason is the same one that used to drive birth rates before the welfare state: social security—but not in the financial sense.

Israelis live surrounded by neighbors who not only want to destroy their state but to kill them and their children—and who are actively trying to do so. That’s a very different situation from other countries with hostile neighbors, like Ukraine. Putin wants to destroy the Ukrainian state, but he isn’t aiming to physically eliminate all Ukrainians.

Israelis understand that to survive—not just as a nation, but as individuals—they must be collectively strong, stronger than all their neighbors combined. And strength, among other things, lies in numbers.

That’s why other developed countries can’t simply copy Israel’s fertility “success.” To do that, they’d have to replicate not ultra-Orthodox faith, but an ultra-hostile environment.

So, is there a future for humanity? Is there a way to reverse the fertility decline?

Possibly—but most people wouldn’t like it.

First, let’s be clear about what won’t work.

Subsidies won’t work: they can’t possibly cover even a quarter of the direct costs of raising a child, let alone the indirect ones. More importantly, money isn’t the main issue. The global data is clear: the richer a country gets, the lower its fertility. When people become reasonably well-off, their “investment strategy” shifts from children to pension plans, whether private or public.

Raising men’s wages so their wives can stay home won’t help either. As we’ve seen, when women have the financial freedom not to work, many still don’t choose to have more kids—they choose other things. The maternal instinct exists, but for many women it becomes dormant after the first or second child. When given options, people choose differently. Some women want more children, others prefer careers or simply a more enjoyable lifestyle—and not because of liberal propaganda, but because people’s preferences genuinely vary.

Abortion bans won’t help either. In fact, they could even depress birth rates in the long term. Abortion is a last resort for those who don’t want children—at least at that moment—but failed to prevent pregnancy. Nobody wants to have an abortion. Some, when faced with the option, decide to keep the baby. But if abortion becomes unavailable, those who don’t want children will simply become more careful, removing that last-minute decision point entirely.

Look at South Korea. Abortion was only decriminalized in 2021, after the Constitutional Court ruled the ban unconstitutional. But the ban didn’t stop fertility from dropping: it fell below 2 in 1984, and below 1 in 2018.

So what can be done instead?

There are two ways to approach the problem: from the demand side and from the supply side.

Let’s start with demand—that is, ways to increase people’s desire to have babies.

Here, our options are limited. Dismantling social security along with a simultaneous ban on private retirement plans and private investments might help—but that’s not exactly realistic. Neither is another radical idea: destroying pediatric care. (Though RFK Jr., with his push against child vaccinations, is—fertility-wise—arguably moving in the “right” direction.)

But if we ever manage to colonize other star systems, the problem may solve itself. Life on the outer worlds will likely be even more dangerous and unpredictable than life in today’s Israel—at least for the first generations of settlers—and people may respond by investing in the future of their settlements the same way early societies did: by having more children.

Now, the supply side—measures that might help people maintain their preferred lifestyle while having more kids.

Most of what follows will anger conservatives, liberals, or both.

We could start by dismantling zoning regulations to dramatically increase the supply of affordable housing—not just for “vulnerable groups” but for everyone. If we build many more homes and more families can afford a four-bedroom house, some might decide to have one or two more kids.

Child safety laws are another obstacle: things like mandatory car seats discourage families from having a third child, because they physically don’t fit in most cars.

Still, neither bigger homes nor more backseats will, on their own, push fertility to 2+ children per family. The biggest hurdle isn’t space—it’s time.

The measures that could really help, as controversial as it sounds, would allow parents to spend less time with their children. This is where culture plays a decisive role.

The modern concept of childhood is a 19th-century invention. Before that, children didn’t receive special treatment. They weren’t required to study for 8, 10, or 12 years. They could work from a young age. They could go outside unsupervised. Their safety was their parents’ responsibility, not the state’s.

Today, almost every country mandates extended periods of formal education. Children can’t legally work until they’re 15 or 16. In most Western countries, if authorities discover that a 10- or 12-year-old is playing outside or staying home alone, they can take custody away from the parents.

All these rules force parents to spend more time with their children than many want to. Liberalizing these laws would ease the burden—especially if paired with licensing reform.

The youngest professionals today are software developers, because becoming a programmer doesn’t legally require a high school diploma or vocational certificate. If mandatory education ended at 12, child labor laws were relaxed, apprenticeships fully legalized, and non-hazardous jobs freed from state licensing, many young adults could be working in jobs they actually enjoy by age 15 or 16—possibly having tried two or three fields already.

Never before have people started working so late. And never before has it been so easy to learn a trade: today, YouTube can teach you the fundamentals of any profession—from plumbing to rocket science—with dozens of channels per field.

By 17 or 18, young adults could already be living independently (assuming radical zoning reform)—the dream of nearly every teenager and their parents. Many could even have families of their own.

When young people live with their parents until mid-twenties or longer, as modern average Americans and Europeans do, they don’t have children themselves and make having new ones more difficult for the parents.

Another way to free up parent’s time and cut their optional cost of having children is to ease immigration restrictions on surrogate mothers and nannies from the poorest countries, requiring them to work in these roles for several years under threat of deportation.

Still another: destigmatize and deregulate boarding schools. Make it easy for anyone without a criminal record to open one. Make them widespread, affordable, and socially acceptable. Get boarder school alumni Boris Johnson and Harry Potter to promote them.

The problem is, every one of these proposals would be dead on arrival in any modern parliament. The only places where the political climate isn’t completely hostile to such measures are in the Gulf states. We’ll probably see some cautious steps in that direction there over the next decade or two.

As for the rest of the world? It’ll have to wait for a technological breakthrough. Elon Musk would do more for natalism if, instead of simply promoting it, he concentrated on mass-producing artificial wombs and robot nannies.

Sources:

https://www.bostonglobe.com/2025/05/04/opinion/trump-5000-baby-bonus/

https://www.lendingtree.com/debt-consolidation/raising-a-child-study/

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/may/17/rethink-what-we-expect-from-parents-norway-grapple-with-falling-birthrate

https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2024/07/25/demographic-and-economic-characteristics-of-adults-50-and-older-without-children/

https://news.ubc.ca/2018/06/dads-often-earn-more-even-if-theyre-not-harder-workers/

https://www.newsweek.com/motherhood-penalty-report-gender-pay-gap-debate-fatherhood-bonus-1919965

https://www.weforum.org/stories/2017/05/why-mothers-are-less-wealthy-than-women-without-children/

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11205-015-1102-7

https://ifstudies.org/blog/the-real-housewives-of-america-dads-income-and-moms-work

https://www.deseret.com/2019/1/24/20664077/rich-and-poor-married-moms-are-more-likely-to-stay-at-home-with-the-kids-but-for-entirely-different/

https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2014/04/08/after-decades-of-decline-a-rise-in-stay-at-home-mothers/

https://www.thesocialhistorian.com/womens-occupations/

https://penntoday.upenn.edu/news/how-appliance-boom-moved-more-women-workforce

https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/nancy-folbre-unproductivehousewife-1991/76419012

https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistory/comments/15xuj3o/was_it_uncommon_in_the_1930s_for_someones_mother/

https://journeys.dartmouth.edu/censushistory/2016/11/03/working-mothers-and-fathers-in-the-united-states-20th-century/

https://history.stackexchange.com/questions/33493/what-is-the-history-of-stay-at-home-moms

https://www.statista.com/statistics/241530/birth-rate-by-family-income-in-the-us/

https://foreignpolicy.com/2025/05/14/birthrates-israel-demographics-religion-nationalism-world-population

https://archive.ph/Pzq6E

https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2021/05/11/jewish-demographics/

https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w33311/w33311.pdf

https://www.visualcapitalist.com/ranked-european-countries-by-the-average-age-adults-move-out/

https://www.deseret.com/u-s-world/2024/2/9/24062898/gen-z-and-millennials-move-back-home/

https://salarship.com/article/average-age-move-out/

You missed another historical benefit: families were producing their own labor force. Starting from babysitting younger siblings and running choirs, up to working on a farm or even factory.

Спасибо, thought provoking!

Заметки на полях: В Новой Зеландии аборты декрминализировали тоже прям совсем недавно, после 2019. Не уверен есть ли исследования по тому, как это сказалось на рождаемости. Ну и у нас тоже достаточно идиотские законы есть по "заботе" о детях. До 14(!) лет ребенок не может остаться один дома.